THE MANY SAINTS OF MISOGYNY

BA Hons Photography, 2022

The flashpoint case of Sarah Everard, followed by Sabina Nessa, Bibaa Henry and Nicola Smallman, and Bobbi Anne MacLoed brought the word misogyny into the mainstream more than ever before. It evolved. It became far more than its ‘naive’ concept and basic dictionary definition; a hatred of women harboured by men, an explanation that was dangerously limiting and prevented the identification of misogynistic behaviour. Misogyny mutates, much like the variants that grew from the COVID crisis, which in itself was responsible for a rise in domestic abuse cases during lockdowns.

This ignited a wave of social movements, some of which were all too familiar. #MeToo, #ReclaimTheStreets, #ReclaimTheNight, #TextMeWhenYouGetHome; these hashtags went viral on social media and became a loudspeaker for women across the world to share their own experiences and express their outrage at the lack of progress in tackling these systemic societal issues. Offline, vigils took place; some only further fanning the flames of misogyny. At Sarah Everad’s vigil, there was unnecessarily aggressive and violent treatment of peaceful female protestors by male police officers. At Sabina Nessa’s, heart-shaped rape alarms were handed out. Protestors rejected this, arguing that placing responsibility onto women was not the answer. “You’re giving me a girly cutesy alarm and asking me to wait for some knight in shining armour to rescue me. It’s missing the point, it’s not protection. It’s calling for someone else to help you. Real protection comes from reforming the criminal justice system. Putting the onus of women being murdered on women takes away from what police are responsible for, and the fact it’s men killing us.”

It is the question that keeps arising. Why is that our behaviour that has to change to prevent us being assaulted or killed? Why is female safety solely the responsibility of women?

The women photographed for this project reflect the stories of the women who have experienced gender-based violence and oppression. In stark comparison to being judged, they are reimagined as saints to invert judgement; judging those who judge them.

The Many Saints of Misogyny are intended to be the patron saints of safety, a sisterhood of sanctity; our Saint of the Keys, Saint of Drink Spiking, Saint of Domestic Abuse. Sent as mediators, they remind us of the sufferings they endure so that we may effect change so that others do not suffer the same.

We are the many saints of Misogony. It is our responsibility to change the equilibrium.

“Or do you not know that the saints will judge the world?” (1 Corinthians 6:2)

GOING NOWHERE

A portrait of Gatwick Airport in the Pandemic

A TELEPHONE CALL

BA Hons Photography, 2020

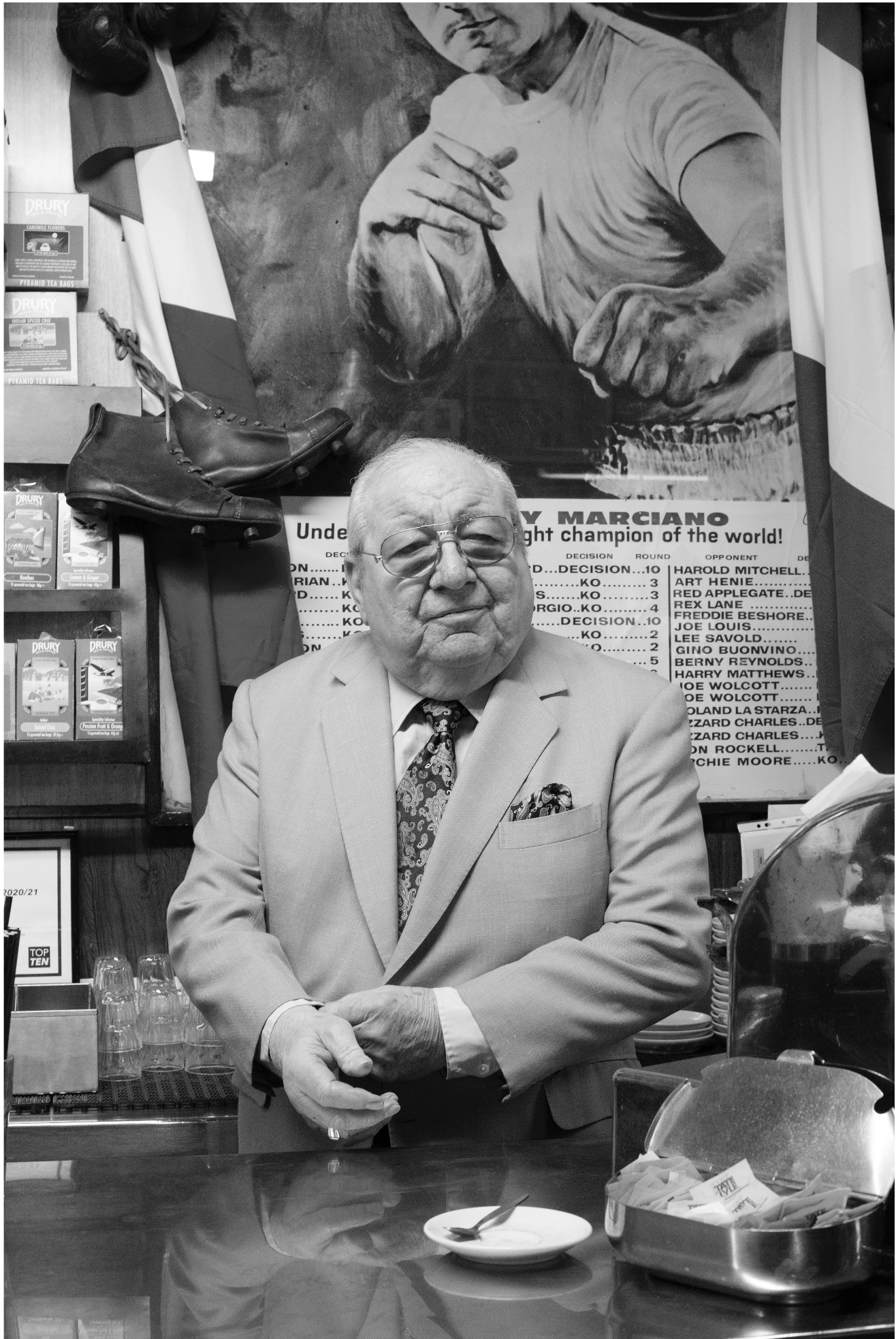

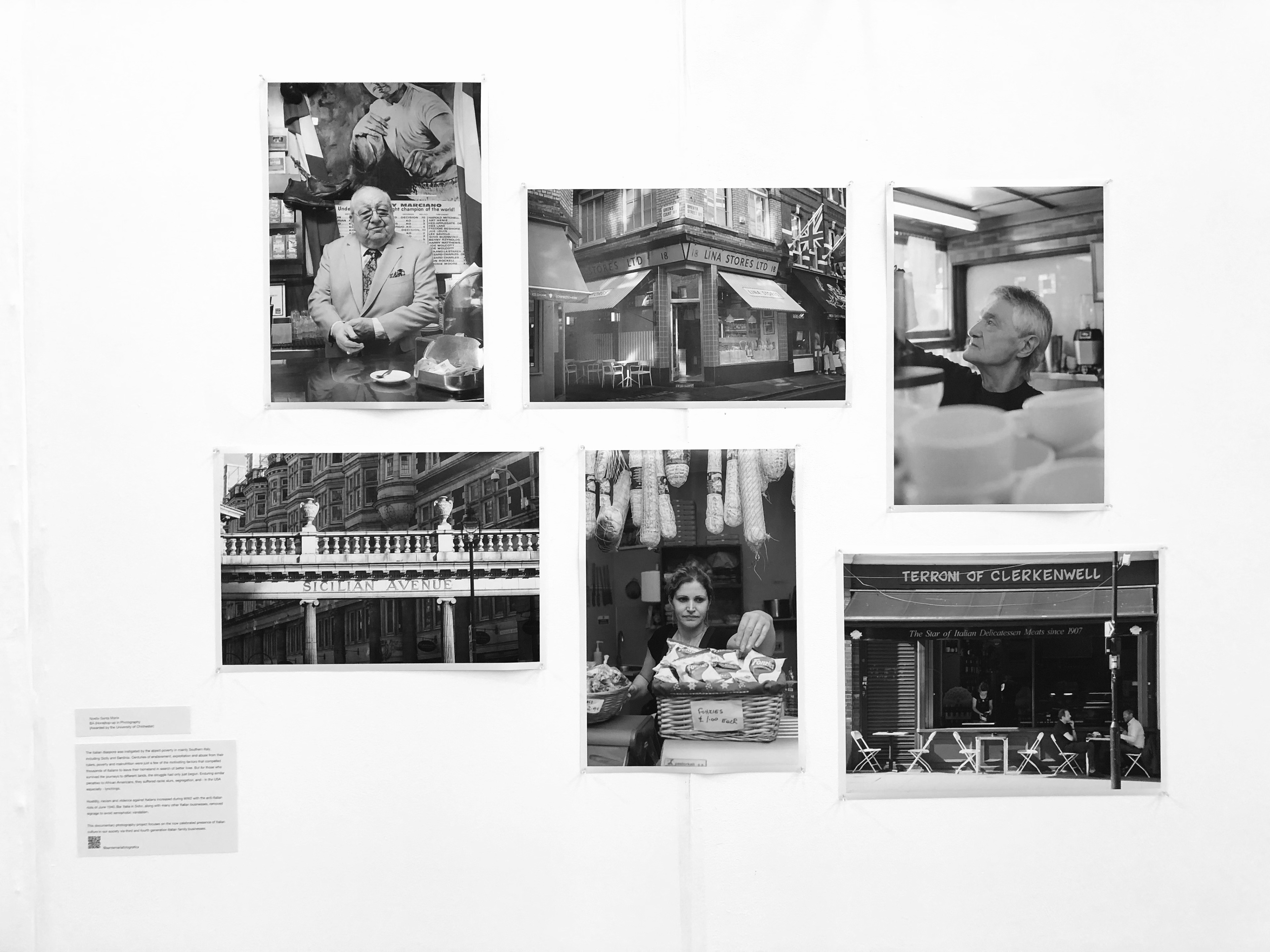

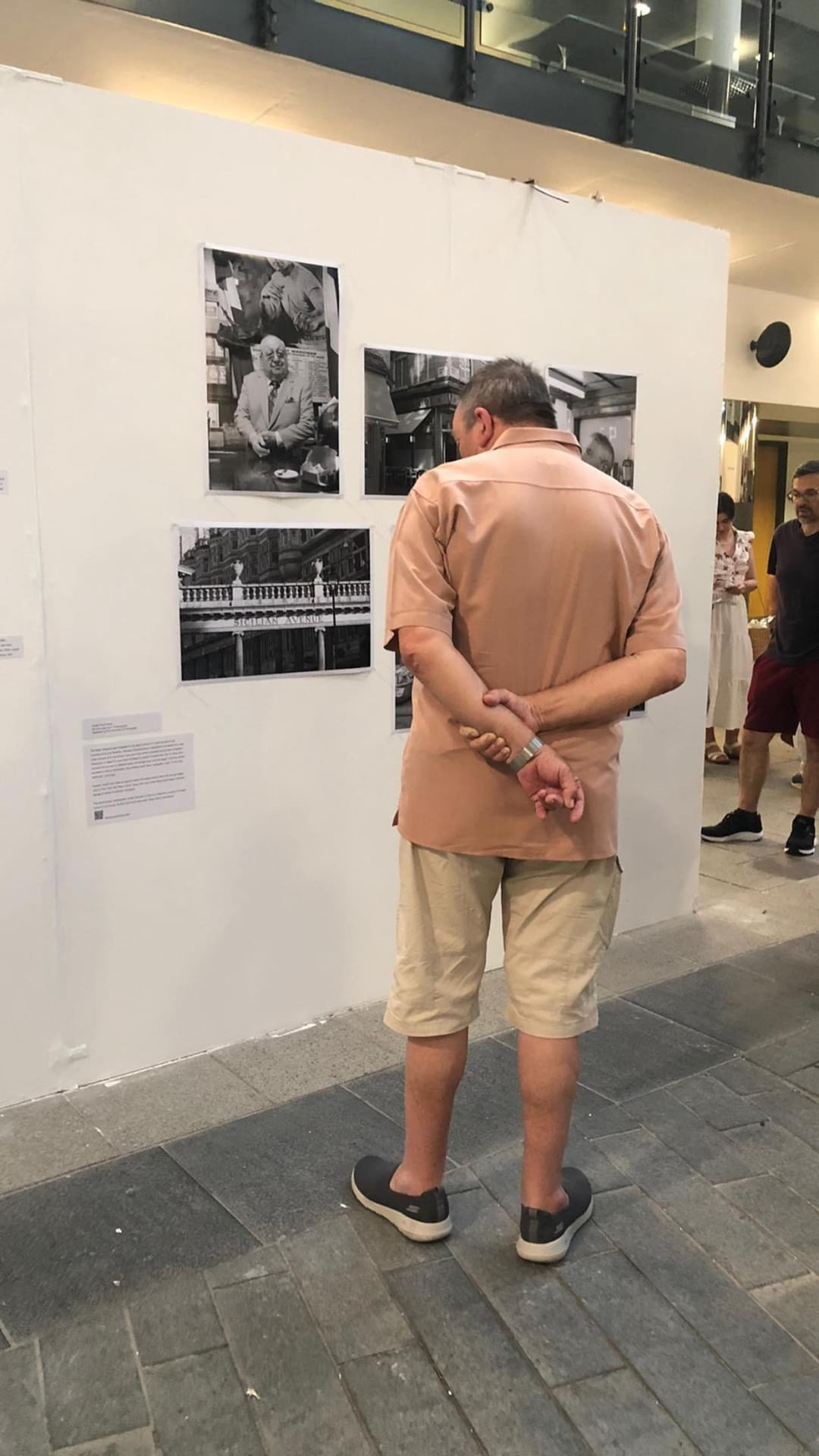

ITALIANS IN LONDON

BA Hons Photographer Final Major Project, June 2022

The Italian diaspora was instigated by the abject poverty in mainly Southern Italy, including Sicily and Sardinia. Centuries of enslavement, exploitation and abuse from their rulers, poverty and malnutrition were just a few of the motivating factors that compelled thousands of Italians to leave their homeland in search of better lives. But for those who survived the journeys to different lands, the struggle had only just begun. Enduring similar penalties to African Americans, they suffered racist slurs, segregation, and - in the USA especially - lynchings.

Hostility, racism and violence against Italians increased during WW2 with the anti-Italian riots of June 1940. Bar Italia in Soho, along with many other Italian businesses, removed signage to avoid xenophobic vandalism.

This documentary photography project focuses on the now celebrated presence of Italian culture in our society via third and fourth generation Italian family businesses.

WHAT LIES BENEATH

From Disorders to Dior, Autism to Aquascutum, Bipolar to Burberry: a study of labels in capitalist culture.

A philosophical photographic project that explores society’s obsession with labels and categorisation. The systemic force of this obsession shapes our identities and dictates our conduct from the cradle to the grave, determining our worth based on which label we are assigned and which category we are shoe-horned into.

My concept for this project was to challenge, deconstruct and reverse the stigmatic, taboo, and negative labels society assigns to us. Progress is slow in changing deeply entrenched negative perceptions of psychological labels, or those of sexual orientation. Many find it hard to bear the negative connotations those labels bring, thereby exacerbating their original struggle to ‘fit in’, be ‘normal’ or meet expectations. My work juxtaposes these with the more coveted, ‘positive’ labels, which society uses to tell us we are acceptable, popular, desirable, and which elevate our social status, ergo placing a higher value on our existence, and increasing our own self-worth via the adoption and display of designer labels.

SPACE

For this project, I explored theoretical and philosophical studies of architectural space, including existentialism, phenomenology, and the scopophilic experiential properties of thoughts, desires, feelings and perceptions associated with the philosophical concept of qualia. This led me to consider oneiric space; that is, where the space relates to dreams, or dreaming, explored by Bachelard in The Poetics of Space: “The values that belong to daydreaming mark humanity in its depths. Daydreaming even has a privilege of autovalorization. It derives direct pleasure from it’s own being…” The philosopher Karsten Harries, as recounted by Pallasmaa, reiterated Bachelard’s view of the psychological role of architecture: “Architecture helps to replace meaningless reality with a theatrically, or rather architecturally, transformed reality, which draws us in, and as we surrender to it, grants us an illusion of meaning…”.

Staircases are spaces that are used as a means of transition to other spaces. They exist as one space that provides vertical access to another. A staircase can exist as a simple, everyday functional object that goes unnoticed and is for the most part meaningless to the user; but it is often used for far more than what it was designed for. Staircases can be a space that provide us with a place to sit, eat, drink, socialise, talk, or even spectate from an elevated position (they are not dissimilar to the design of an amphitheatre).

They can also be metaphorical, symbolising ascendance or a fall from grace. An example of a staircase used to symbolise this is in the famous end scene of the 1954 Billy Wilder film Sunset Boulevard; where faded silent movie star Norma Desmond descends slowly down her grand staircase, at the bottom of which police officers wait to arrest her – a metaphor for her downward spiral and descent from the Hollywood elite, the great height of fame. A descent not only physical, but also symbolic of her further descent into madness.

Staircases can also represent aspirations, or the overcoming of obstacles – climbing to the top of a staircase gives feelings of success, of reaching the top, and the rewards of an elevated position after a long, arduous climb. Elevators, states Bachelard in The Poetics of Space, ‘do away with the heroism of stair climbing.’ Juhani Pallasmaa echoes Bachelard’s sentiment here, stating in Stairways of the Mind (2000) that ‘the climbing of steps reflects an archetypal psychic longing to approach the heavenly sphere of the cosmos.’ This is of particular interest where this space is denied; for example, where a rope is across the steps, forbidding any further climbing (see one of the final images).

In Existence, Space and Architecture (1971), Norberg-Schulz refers to staircases as “…built to conquer a difference of levels…giving the feeling of victory over gravity.” He describes spiral staircases as “an unusual fascination…where one really experiences rising up along the vertical axis.” He goes on to acknowledge that “urban stairs have often served as the link between a sanctuary at the top and a crowded piazza at the bottom, thereby concretizing the transition from one existential level to another.”

Stairs are a common symbol of heaven and hell; the ascendance into the heavens, or descent into hell (in architectural terms, the attic or the cellar according to Bachelard in The Poetics of Space). “Ascending stairs culminate in heaven, whereas descending stairs eventually lead down to the Underworld.” (Pallasmaa).

Class, status and hierarchy also have a connection with staircases; for example, the well known phrase ‘life below stairs’ was used to describe the low standing and humble social position of those in servitude. Servants would be limited to using the unornamented back stairs to avoid being seen by their superiors, forbidden to enter the spaces designed for the elite and aristocratic types and for whom the grand staircases were reserved. “Throughout history” writes Pallasmaa, “the stair has represented cosmological ideas and and spiritual aspirations, power and authority, prestige and status, hierarchy and classification.” Pallasmaa also points out the primitive classification system of flora and fauna of Noah’s ark, noting that winners of sports events continue to be awarded on a similar stair of classification.

Space can be presented to the viewer as a place to daydream; a form of escapism. This is not limited to random daydreaming; but also ties into nostalgia, of memory. “Here, space is everything. For time ceases to quicken memory…memories are motionless, and the more securely they are fixed in space, the sounder they are.” (Bachelard, 1958). What attracted me to photograph stairs and represent them as a space were my own memories from childhood; a sacred space where I would find peace, escape, or adventure.

GOING NOWHERE